Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'writing'.

-

Evolving trends in pre-nineteenth century Sikh Historiography. The primary sphere of reverence, in Sikh academia, is the Adi Guru Granth Sahib Ji with second and tertiary accompaniments being the Dasam Granth and the compositions of Bhai Nand Lal. The latter are noteworthy in many respects. They establish a timeless connection between the reader and writer across several milieus, yet offer only tantalizing glimpses into the lives of the Gurus.' Fluidly focusing upon the Gurus' message, the aforementioned texts lack a cohesive narrative detailing who they where. To ameliorate just such a situation the Sikhs, as a whole, had to parent several distinct genres of literature which would not only detail the birth of their ethos, but also of their evolution under the sacrosanct Gurus. The primary corpus of these genres would not focus upon the tenets, and tutorials, of the faith but upon the lives of the promulgators of the faith itself! Not only would these genres have to incorporate the nuanced orthodoxy of the faith, Per se, but also define the Sikhs as a faith, and holistic force in light of their association with the Gurus. To this end three new literary models were born. The initial Janamsaakhi tradition, followed by the multi-faceted Gurbilas series and the ever-evolving Rehitnamas. The Janamsaakhis' (or tales of birth) incorporate a triumvirate design. They solely concentrate upon the life of Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) via specifying it in three general Parochial's. Birth, voyages and settlement. Janamsaakhis,' it seems, were written with three broad intentions. One, to provide an emulative biography of the Guru. Two, to grant Sikhs and non-Sikhs alike a literary darsan (glimpse) of the Guru. And three, to provide an exegetical source of Gurbani via incorporating contextual and environmental influences. The bibliography of these Saakhis consist of oral folklore prevalent in the Guru-era Punjab. Mcleod notes that despite the significant time lapses, prevalent between the writing of each Saakhi, the genre carries an authentic ring to it (1). Significant exegetical evolutions, and re-telling's penultimately catalysed in notable differences in each Saakhi. Plausibly nowhere is the latter more evident, than in the hierarchical number of Saakhis' which presently exist. The Bhai Bala Janamsaakhi claims to be the foremost manuscript of the genre. It's claims are evidenced by the fact that it has become a traditional component of many Sikh orders. The schismatic Meharbaan Janamsaakhi can be said to be the second oldest, but has been discarded due to it's perceived unorthodox content; whilst the Bhai Mani Singh Janamsaakhi is categorised as being the third oldest and authoritarian. Other Janamsaakhis' also exist with the most mooted being the recent B40 Janamsaakhi. Yet as Surjit Singh Hans and W. Owen Cole elucidate each Saakhi should be analysed carefully for veracity and authenticity. Cole is at pains to highlight that no scriptural, or preliminary, Sikh text mentions the existence of Bhai Bala. The fact that the latter's Saakhi eulogizes Baba Hindal, and Bhagat Kabir, at the expense of Guru Nanak Dev Ji makes it's relevance questionable. The Meharbaan Saakhi presents a coloured vision of events, especially in light of the fact that the author's father was opposed to the orthodox lineage of Guruship. Summarily, the criteria for essaying each Janamsaakhi might vary from manuscript to manuscript, but the genre represents the earliest pivotal point in Sikh literature. The Gurbilas series shows a poetic, and structural, strain derived from the Janamsaakhis but radically differs in many respects. A majority of the genre focuses on the life of one individual, although Kesar Singh Chibber's Bansavalinama Dasan Patshian Ka, runs as an anomaly to the genre's Status quo. The primary cataloguing point for this diverse genre hinges on the mythological, and political, content of each manuscript. Chibber's Brahmin ancestry stood him in an instrumental stead to utilise ancient Puranic, and mythological texts, in order to construct a magnetic genealogy of the Gurus.' Yet even his work is without bias. Reaching out to the dominant Hindu majority he rues the over-dominance of stratified Jatts, and Dalits, in the Khalsa whilst exposing Islam to a microscopic scrutiny. Simultaneously he mentions Akali-Nihung Guru Gobind Singh Ji as having manifested Kalika, for military aide, and the Gurus' being honorific avatars of Vishnu. With the commencement of the Sikh Reformative era, it's no wonder his work fell out of use. But Chibber's work is profoundly prolific. In 2,564 stanzas, and 14 chapters, he relates significant events from the lives of the ten Gurus', Banda Singh Bahadur, Ajit Singh (adopted son of Mata Sundar Kaur), and the life of the matriarchal Mata herself. Later Gurbilas additions would follow an emulative course, although fundamental differences would become significant in each serial generation. Gurbilas Patshai Chevin (sixth) orbits the life of Guru Hargobind Sahib Ji. It encapsulates the latter's birth, father's life, marriage, battles and other impactive events which shaped the subject's life. Despite chronological errors, the work is a well-grounded piece authentically narrating the important events in the life of the Guru. Koer Singh's Gurbilas Patshai Dasvin (tenth) completed in 1751 C.E. (the author was a confidant of Akali-Nihung Mani Singh Ji) is categorised as being the most inauthentic of the series. The author makes no avid distinction between myth, parable and reality in his narrative. He perpetually misplaces dates and implies (insubstantially) that the tenth Guru undertook a journey to Ayodhya. Sukkha Singh's emulative text, of the same name, is solely concerned with the Guru's battles and the ethics orbiting the latter's political mindset. All 31 Cantos of his work carry a scholarly ring and avoid the ardent mythologising found in initial texts of the genre. The most aberrant text, in the entire series, is that of Bhai Sobha Ram. His Gurbilas Bhai Sahib Singh Ji Bedi does not draw upon preliminary sources such as the Dasam Granth, and other contemporaneous accounts; but instead focuses on his own observance of Baba Sahib Singh Ji Bedi. The latter was an eighteenth century descendant of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, and an avid player in the politics of Lahore. Ram implies him to be the temporal emulation of Akali-Nihung Guru Gobind Singh Ji, dispatched to coronate Ranjit Singh as the emperor of Punjab. The latter makes evident the political appeal of the work, and one cannot help but wonder if the latter was the sole inspiration for the text's birth. The Rehitnamas are the most divergent of the three genres. They are not exegetical accounts, such as the Janamsaakhis', or even biographical sketches such as the Gurbilas series. They are more de imitatione Gurui, aiming to emulate the conduct of the Gurus' via an indirect mimesis. The Janamsaakhi, and Gurbilas, genres provide a literary darsan of the Gurus' but the Rehitnamas tend to rationalize, and interpret, their actions for the disciple's emulation. The Rehitnamas depict a direct strain of evolution, the genre has a Herculean amount of offshoots and each and every one of the latter depict changing political, and social, trends. Purnima Dhavan notes that the era from 1715-1748 A.D. was important in the evolution of the Rehitnamas. The Khalsa decided to cement an unique and ubiquitous identity, and the Rehitnamas became pivotal judge of it's social and political conduct. She provides an interesting example of this evolution orbiting military service for the Khalsa in the eighteenth century. Prahlaad Singh's Rehitnama warns, '...that the Sikh who bows his head to one who adorns a skull-cap (Muslim) will dwell in hell, but the Sikh who worships the Akal-Purakh will carry the benefits of his entire clan.' (2) Simultaneous Rehitnamas' also carry a similar tone, leading one to conclude that the eighteenth century ascension of the Khalsa polity played an unique role in the formation of each Rehitnama. The writers forewarned against the events which they witnessed, i.e. Khalsa adherents becoming mercenaries for Islamic rulers (Jassa Singh Ramgarhia and Adina Beg). The latter was construed as being a grievous trespass. Especially in an era where the Khalsa was warring for political autonomy from radical Islam. The Chaupa Singh Rehitnama represents another facet of the genre. The separation of Khalsa socialism, and political precepts, from that of the contemporaneous Islamic polity. 'The rulers of the world should serve as lights, yet nowhere had a lamp been lit, nowhere could a light be seen. And so these rulers were driven out in order that the panth might rule in their place. He bestowed authority on the panth in order that it might take revenge on the alien Muslims (maleccha), ending their rule once and for all.' (3) The latter carries an impertinent warning for Khalsa rulers. Just as Islamic tyranny was brought to heel, so would the Khalsa state if it emulated the latter. One can easily conclude that no Rehitnama is definite. Whereas the genre, in the eighteenth century, concentrated on martial pursuits and politics; it's modern counterpart is more concerned with spirituality and day-to-day conduct. Thus, they reflect the periodical psyche of the Khalsa as it slowly evolves. They offer no firm insight into the perpetual, non-changing, psyche of the Khalsa because the latter does not exist. Unlike the Gurbilas genre however, they do tend to draw material from Gurbani and are often at pains to pinpoint their relevance to the latter. Whereas the Janamsaakhis, and the Gurbilas, are reminiscent of the past; the Rehitnama is a continuing genre ever-changing from milieu to milieu. Sources: (1) Fenech, E. L; Singh P. (2014) The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies.Oxford University Press, NY, USA, pg. 183. (2) Dhavan P. (2011) When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition. Oxford University Press, NY, USA, pg. 78. Source: http://tisarpanth.blogspot.co.nz/2014/06/sikh-literature-in-pre-colonial-india.html

- 1 reply

-

2

-

- sikh literature

- genres

- (and 8 more)

-

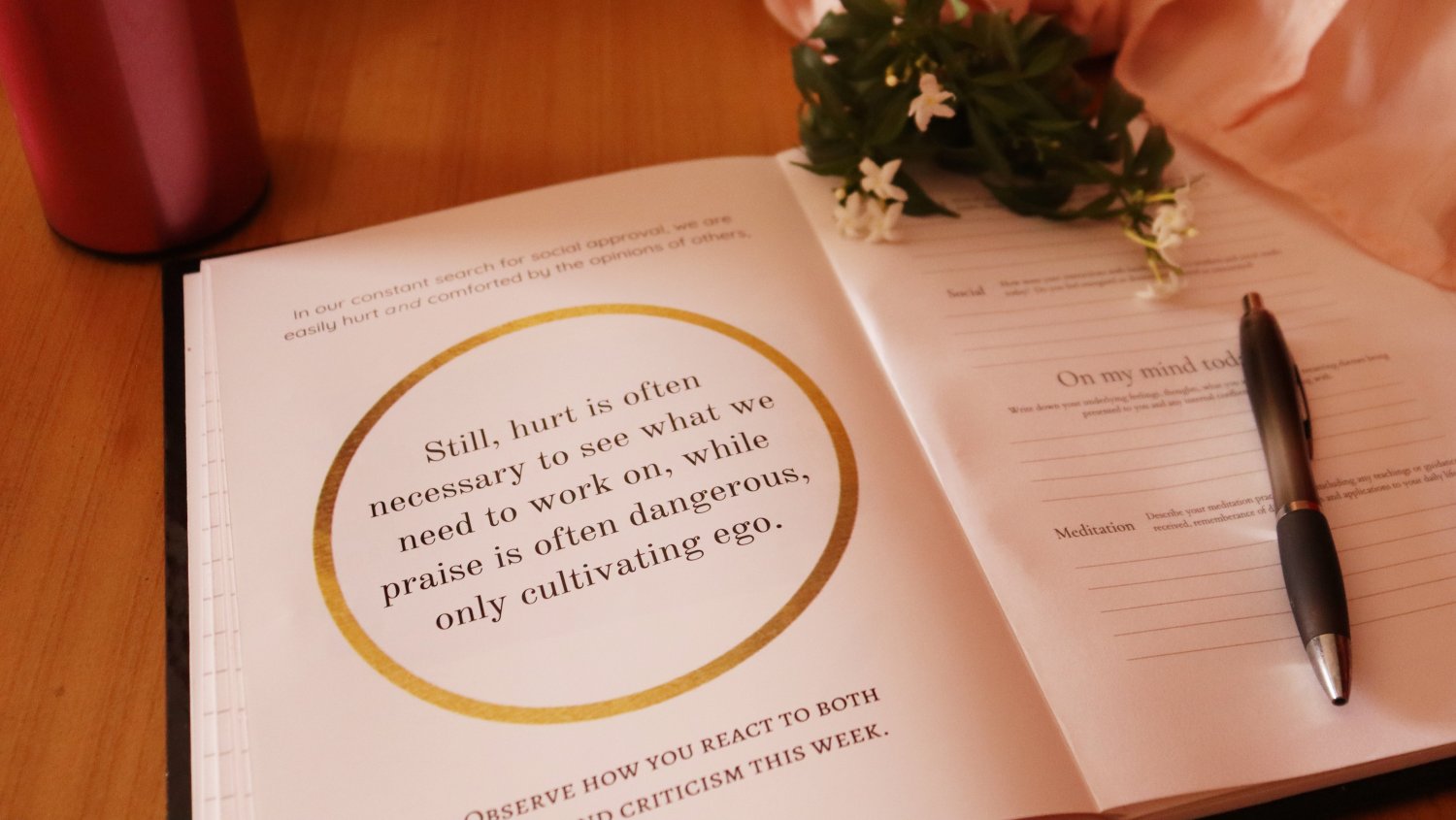

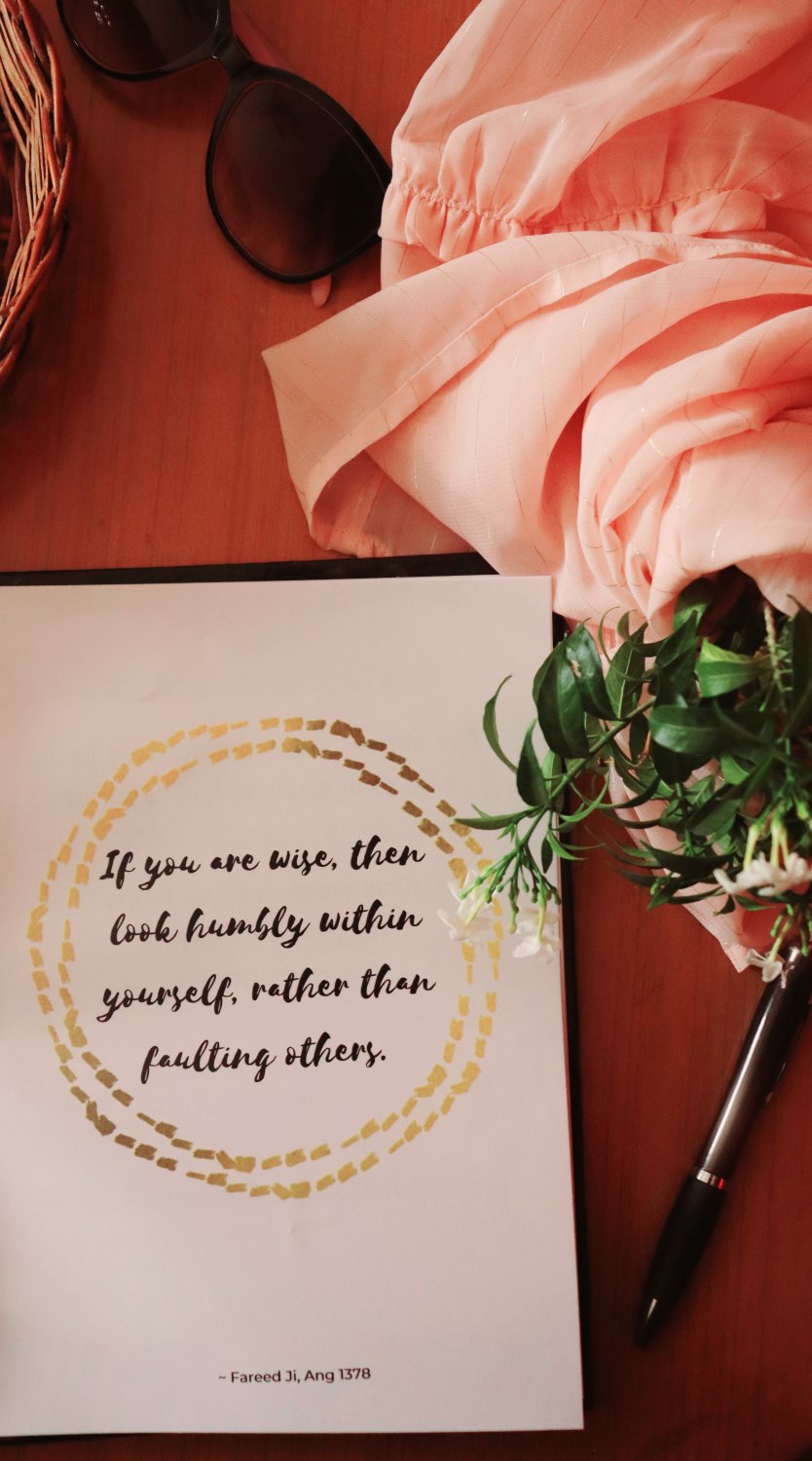

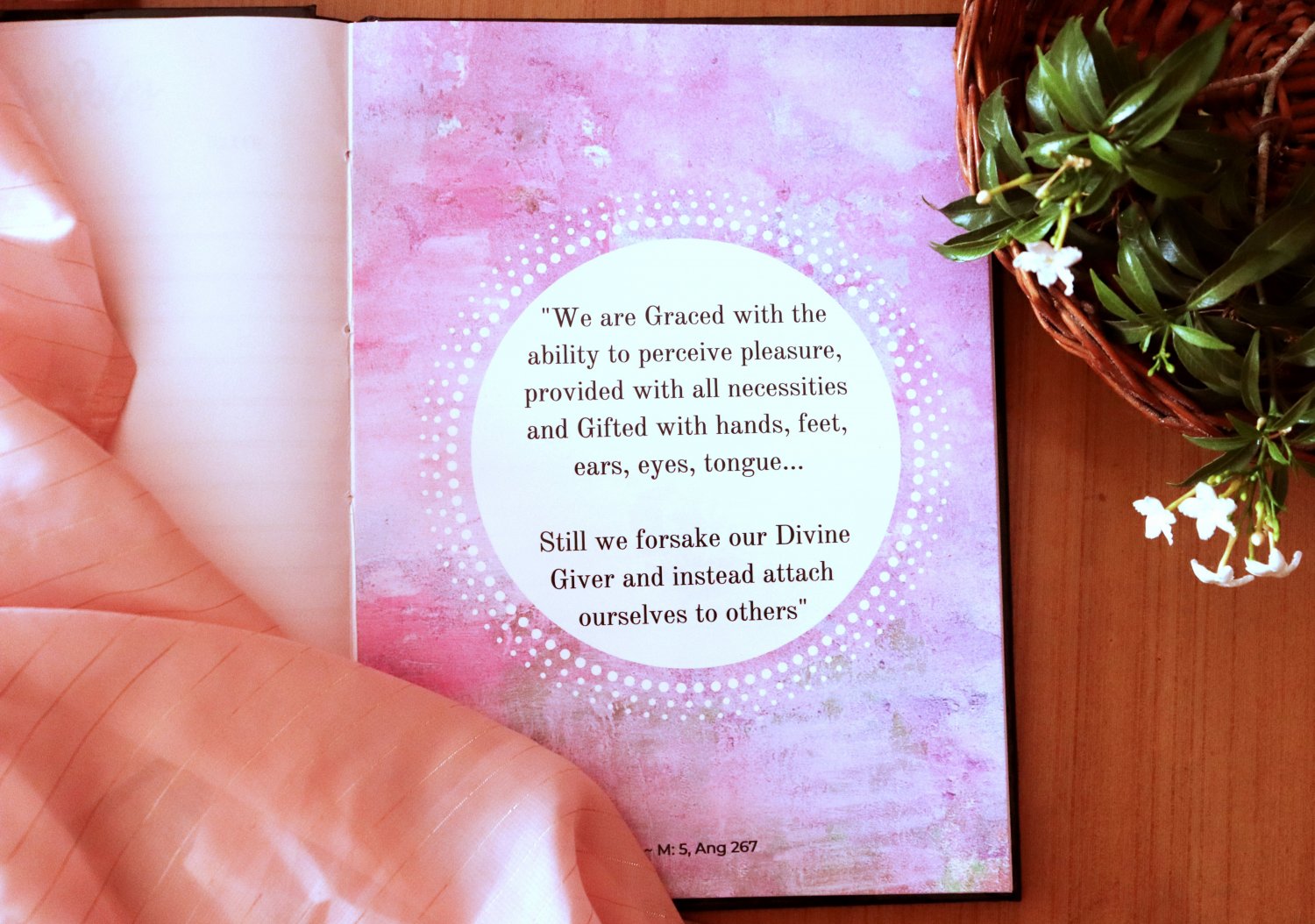

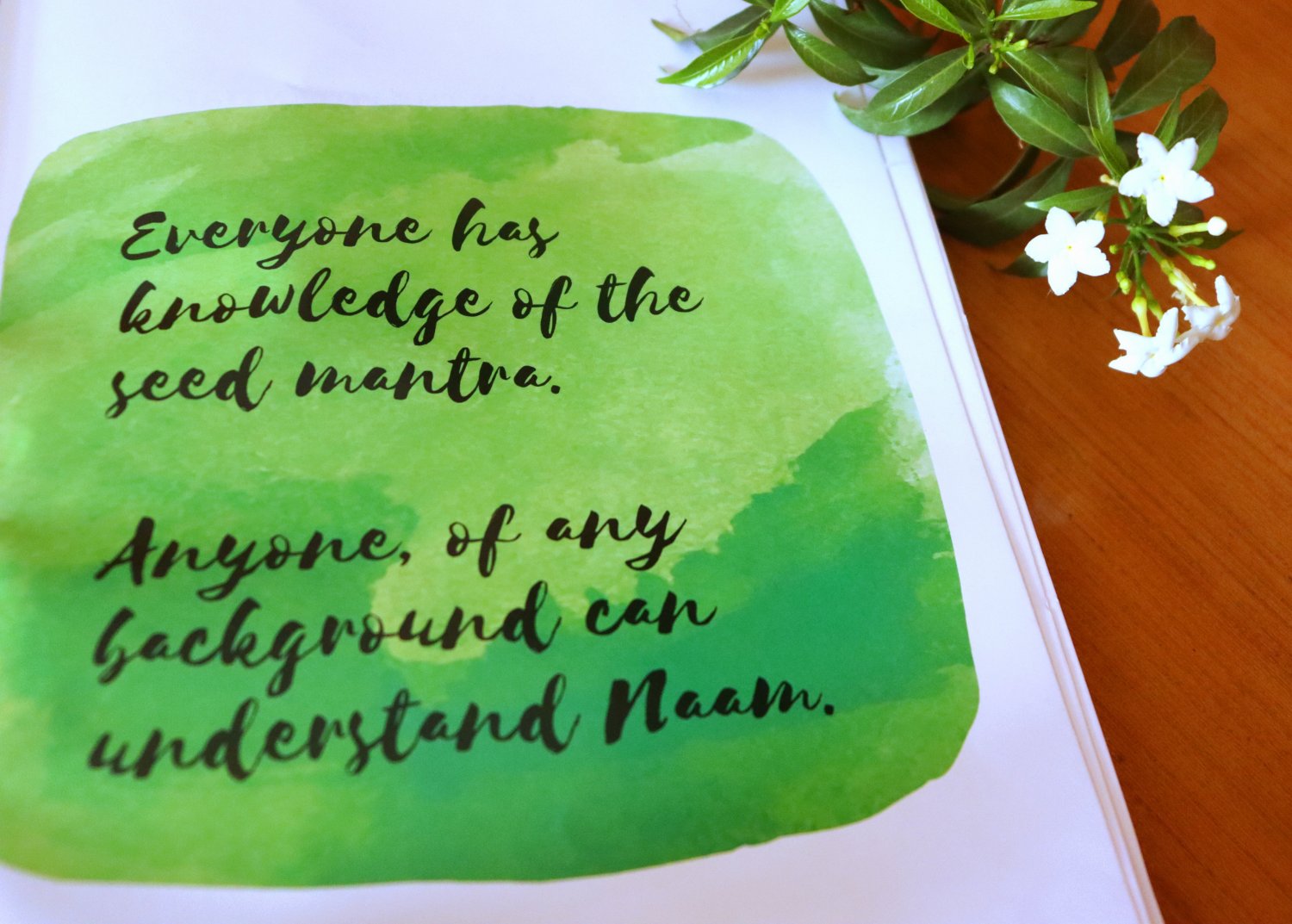

Vaheguru Ji ka Khalsa Vaheguru Ji ki Fateh Daas has recently created a Sikh Reflection Journal. This is a guided meditation journal based on Gurbani, however it is written so that anyone, of any spiritual background and any spiritual level can use (Gurmat is truely universal). Its to be used as a tool alongside daily gurbani khoj to help improve our own spiritual practices and apply Gurbani in our lives. This is not intended as a profitable business, rather to improve the quality of sangat veechar and develop our own relationships with Gurbani. It has been selling well in Australia, Canada, UK, USA, India (special price) and Malaysia. We have only 50 copies left ji. If you would like a copy or as a gift, the direct link is: www.thebestlifeot.company.site. There is a video look through of the journal on YouTube: https://youtu.be/2JNy5ahRehQQ As a topic of discussion, how do you feel about journaling and Sikhi? Do you do it often? How has it helped you? I personally stopped a while ago because my veechar were becoming really complex and abstract. Blank lines gave me no guidance and I would go off topic, start writing about worldly things, then feel defeated that I had wasted this time just writing, but for what purpose... Tried finding a Sikhi guided journal but there were none. Christians have these amazing prayer journals. There are also Quaran and Buddhism guided journals too... Shouldn't we be putting more effort into such tools? Thoughts?

-

This is a story I have been working on. Please criticise it as you see fit. Warriors of Chandi. Despite his aching bones, the old warrior urged his mount on faster. The hunt had begun days back and evolved into a tedious pursuit. The quarry was in his sights, and he was not about to forfeit the honour it would bring him. For a long time now, he had been mounted. His back moaned in protest whilst his hips begged for relief. But relief there would be not! No man worth his salt would surrender now. Not when the mighty buck, prince of the woods was slowly wearying of protest. As if reading his thoughts, the aristocratic bovine halted. Turning around it took the measure of its foe. The old man too halted, his horse whinnying in protest. With a quick kick he silenced it, not wishing to disturb the now wearied prince. Slowly circling each other, prey and predator, the man and beast considered their options. Would the thrust of cold metal triumph, or would the antlers of the buck grown over months rend the hunter limb to limb? Than as if fate had tired of the debacle playing amongst Mother Nature, a sudden flight of a sparrow amidst the trees startled both. Grasping the moment both the monarch and the peasant flew towards each other. Their speed aided by the intensity of the moment, blood rushing in the ears of both and then with a mighty leap both were at each other. The young hunters, resting in their saddles, were startled awake by a mighty roar. Looking about they heard the whimpers of a beast in the throes of death. Smiling they turned back towards the village. Nihal Singh followed suite. The old Nihung was tired in both spirit and limb. His steed too protested the ardent weight of the buck upon its back, but one kick from its master sufficed to silence it. The mount enjoyed a precarious relationship with its master. In its younger days, when the dew had still tasted fresh, it had carried him into battle. Butting other steeds it had shamed many into submission, but the ways of the two-legged ones stumped it. Rather than shaming the opponent by butting it, or even kicking it, they resorted to steel. And blood had flown as a result. Its first taste of carnage had not been long in coming, perplexed it had later sought out its mates and questioned them over the ways of the two-leggeds. They had only whinnied their perplexity and went back to chewing their grass. The horse was truly getting tedious. It whinnied its protests rendering him deaf. Nihal Singh persevered on however. The hunt was over, but its fruit had to be brought to the camp before nightfall. Otherwise the youngsters would again be given a diet of Sukha. He smiled at the memory. It only made the drinker hungry, and the children had cried their protests the first time. They had soon learned to preserve silence however. Especially when Imperial patrols sortied close to their camps. He silently prayed that the camp was in the same location. Otherwise the buck would start too rot, and where would he be then? ‘So the old tiger still possesses fangs!’ Nihal Singh halted his horse (earning a wholesome round of protests from it) and peered into the underbrush. Several shapes emerged from it, and soon a whole troop of seven Nihungs encircled him. They had only matured last winter, and most hadn’t even earned their farlas yet or been fully bloodied. ‘Useless! Useless the whole lot of you!’ he judged. But his heart was proud. All seven had nearly snatched the buck from his hands; it was only his years of experience in the forests which had given him the upper hand. His mentees cast mock faces at him, expressing distraught and faked anger. ‘We are never too good for you Baba…’ they moaned (at this stage his horse took the cue to start once again), he laughed at their joviality. ‘Come on then’ he ordered ‘back to the palace.’ With the arriving of the hunters, the atmosphere had cleared and finally the smell of food filled the air. For days now no one had eaten, and Baghel could not remember the last time something solid had pleasured his taste-buds. The ‘palace’ as it was known was their camp. Always mobile, they only stayed a week at the most in one region and then set off deeper into the wildness. This had been his way of life since the start, he had known no other. Regarded as being an anomaly of sorts, amongst his fellows, Baghel despite his turban and sword wasn’t a Sikh. He had been a rat of the streets, cast out like some vile vermin from his mother’s womb and destined for a future of thievery, exploitation and violence. His fortunes however had peaked when he had attempted to thieve a blue-clad man. His victim had looked into his eyes before shattering his chartered world with a wholesome smack. To Baghel it had felt like an earthquake. This had been his fist meeting with Nihal Singh, a Sikh fugitive trying to hide amongst the vermin of Lahore. Baghel’s body though reeling from the shock of the blow, had paved the way for his mind to start calculating. He was a fugitive himself, and what more the Sikh could be his protector. Thus what he had done next had surprised even him. Falling to his feet he had begged, cried, and even suspiciously whinnied for Nihal Singh’s companionship. The Nihung had shaken his head and agreed. After all he would be needing a guide to Lahore. That was then, now Baghel was his protector’s apprentice. But whereas the other’s learnt to fight. He was tasked with the kitchen and the governing of the adolescents. Treated as a prince amongst the ‘palace’ his dishes ranged from the mediocre cold to the furnace hot. Yet his patrons tolerated his handiwork, despite later disappearing for prolonged periods of gaseous revilement. Receiving the deer from Nihal Singh, he set to work. A few of the Nihungs joined him. Laughing and gesticulating wildly they recounted their exploits on the game trail. ‘Did you see me?!’ One of them wildly shouted. ‘Oh we saw you alright,’ his companion responded ‘riding as wildly as that fat Mughal we thrashed last summer.’ This earned a riotous acclaim of laughter from his friends, Baghel however chose to remain quiet. Why should he indulge in such mirth? His own exploits of bravery only extended to catching the stray chicken, or balancing the cauldron of hot water which he boiled in the mornings. From the start he had begged Nihal Singh to recruit him amongst his warriors, but the Nihung had refused. ‘You be our woman for now boy,’ the warrior had replied. ‘When the time comes than you shall lift the sword.’ Reminiscing of times past he lifted his head, where was the old dog anyway? Upon entering the camp, Nihal Singh had relieved his burden upon the shoulders of Baghel. The boy had been a miraculous find, a gem amongst the vermin from which he had emerged. Trotting to his tent, he had tied his whinnying steed outside it and himself journeyed to the ‘landlord’s’ tent. Despite his undisputed authority over the 45 residents of the ‘palace’ the ‘landlord’ was the only one who could usurp it. Acknowledging this fateful stint in his affairs, Nihal often appeased him. The ‘landlord’ was a blind old man, born amongst the Sikhs of Guru Teghbahadur he had witnessed the epoch of the Khalsa with his own eyes. In the aftermath he had joined Banda Singh, and then Binod Singh. But the years had not been kind to him and now he was only a former shadow of himself. Burdened by the years he had suffered more loss than even Nihal Singh himself. Wiling away his days, the old man sat beside a fire constantly engrossed in the peculiarities of his own mind. Sensing Nihal Singh’s presence he lifted his hollow eyes and bade him to sit. Silently contemplating the fire both men could have been mistaken for father and son. After a while Nihal Singh broke the silence, ‘did you hear?’ he silently queried. Despite no reaction from his body, the ‘landlord’s’ mind was already at work. Debating whether to reveal what ‘he had heard’ or stay silent. After a pregnant few minutes he replied, ‘it seems what they say is true. There really is a change in affairs.’ Nihal Singh remained silent then, ‘I have no reason to doubt the news. Even the beggars have picked it up, and our men tell us about it. But if so, than why?’ This catalysed in another pregnant silence from the ‘landlord.’ Then grimacing he replied, ‘a battle and a big one.’ Nihal Singh looked at him. He was thunder-struck, it was the umpteenth time that the old man had silenced him with his unexpected intelligence. He started to acknowledge that maybe Baghel was right. Maybe the old man was visited by an agent, or fellow fugitive, in the dead of the night. But how this individual evaded his security measures left him perplexed. Maybe it was a sibling of Banda’s spirits? The old man looked wizened enough to pass for a sorcerer after all. ‘Where?’ he asked curiously. ‘Waan’ his companion replied. ‘Seek Waan.’ Nihal Singh realised anymore talk with the old man would only render the conversation into a riddle. The ‘landlord’ had said his piece. Now it was his turn to discover more. Setting out with the crack of dawn, the next morning, Nihal Singh and his new steed journeyed out of the ‘palace stables.’ Grimacing at being in the saddle again, the old Nihung was thankful for his new mount. Silent and sturdy, it had replaced its much older parent. Silence was the need of the hour, especially if he was to seek out Waan. The morning was shrouded with mist, and a chill was prevalent in the air. Seeking scour amongst the folds of his cloak Nihal Singh trotted on, forward to an ascetic village near the fringes of Lahore. As he journeyed he reflected upon the village’s residences. Headed by an ascetic named Brahm-Dass, it was habited by a mediocre populace of the iconoclastic Udasis. Established by Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s first born son, Sri Chand, their diversity in dress and habit had led to them surviving their brethren’s prosecution. The first time Nihal Singh had encountered Brahm-Dass, the Udasi had proven himself to be the Devil’s advocate. The Nihung’s tutor, and master, Mani Singh had dispatched him to warn the Udasi of a mass movement of troops in his direction. Brahm-Dass had affectionately chuckled at the news, than scratched the messenger’s wounds raw. Their subsequent meetings, over the years, however had panned out and both respected each other although they ardently criticised the other for his defects. Nihal Singh sullenly reflected over his past. The son of a merchant, he had been born with gold in his hands. Pampered and indulged from his birth, he grew up in a feminine environment, especially with his father journeying far and wide. Than upon reaching maturity he fell prey to the whims of a local belle. Entranced by her he had commenced a silent affair. His father however had found out and summoned the girl’s parents. Both lovers had been shamed and with the girl being a Hindu, and Nihal Singh himself being a Muslim, the girl’s parents had been ostracised not only by the regional Muslims, but by also her own kith and kin. As for the young Majnu himself, he had been packed off to Delhi to manage his father’s affairs there. But a usurper had arrived in the form of a brother-in-law. A haughty Pathan, he had taken to expelling and belittling the already embittered Nihal Singh. Thus, the young deputy had taken to escaping into the streets of Delhi and attending the mass spectacles put on for the crowd. A sub-ordinate clerk had once dragged him to an imperial spectacle in central Delhi. The male-dom of the Mughal dynasty had dragged fugitives from the Punjab to Delhi and now prepared to execute them. ‘Banda’s here; kill the infidel! Slaughter him!’ was the crowd’s cry. The Banda, if that was truly his name, himself was a Goliath. Resembling a lion, he had roared out the veracity of his faith and cowered his captors. The young Nihal had watched as more than two hundred fugitives were beheaded over the course of the next few days. Horrified he had escaped the banter and cheers of the crowd and hidden in the slums. It was there he had encountered a Sikh, or the former shadow of one. Living in the guise of a Brahmin beggar, he had regaled Nihal Singh with tales of valour and awe. Ultimately Nihal had made up his mind. He would escape the confines of his family, and also that of his society. Packing his bags he had excused himself from Delhi, for a few days, under the pretext of sickness. Commencing a journey to Amritsar he had encountered a Nihung. Asking for directions he had been dispatched to the city’s central precincts and told to await Mani Singh, a Sikh of almost imperial standing. When Mani Singh had arrived, an awesome spectacle had presented itself before Nihal Singh. Wearing a mesmerising turban, with a curious fan jutting out, and regaled in weaponry Mani Singh was more myth than legend. Sitting down with Nihal, he had commenced an arduous interview of the willing initiate. After forewarning him of the rigours of his chosen path, the sagely Sikh had bade him to join his educational entity in Amritsar. Complying, the next three years of the convert’s life had been spent in a fantasia of education, martiality, spirituality and service. It was then that he had been dispatched to Brahm-Dass to forewarn him of a large cluster of Imperial troops heading his way. The Udasi pedagogue had silently listened to his news than after a while commenced a subtle interrogation. Finally the Udasi had reached his conclusive query, ‘did you sleep with this woman?’ He bluntly asked. Nihal Singh had been affronted and made it evident. The orange-clad devil in front of him had however chuckled, ‘it was not love fool. He had silently whispered, ‘it was only lust.’ Over time Nihal Singh had found himself agreeing more and more with Brahm-Dass’s rationalisation. His youth had been spent in the clutches of possessive women. He had wanted to possess one as a sign of his own prowess. All that however had been snatched from his grasp. Up ahead he heard the rush of a creek. The Udasi hamlet had arrived and he dismounted. Silently treading towards a clearing in the trees, he saw Brahm-Dass meditating. ‘Peace be upon you!’ the Nihung cried, overjoyed at dispelling the Udasi’s peace. ‘May all be destroyed’ the Udasi cursed as he stood up. ‘I dreamt you were coming harbinger of doom!’ He screeched than burst out laughing. Nihal Singh looked on at the spectacle and shook his head; Brahm-Dass was an eccentric mix of mirth and the mundane. Often bursting out in spasms of curses as he pleased. The Udasi bade him sit and offered him food. Still chuckling at his outburst, he quizzed Nihal Singh on his coming.

-

Hello everyone, I'm a writer looking for some help on Sikh names for a forthcoming short story. This forum looks like a friendly place with lots of helpful people, so I thought it'd be a good place to post my question! My story is a science fiction tale set in the far future, and a lot of the characters in it are descendants of Sikh heritage. The hero of my story is a scholar of ancient texts - both holy and historical - and the people of his city come to him for help when no-one else will help them. I need a name that kind of sums up his character. He's learned and quick-thinking. He's not brave like a warrior, but his curiosity to learn more about the unknown, and his devout faith, mean that he does things that others perceive as very brave indeed. Imagine him almost like a Sikh Sherlock Holmes - always thinking, always alert and always ready to use his wits to battle evil and corruption. Any suggestions for a good name for him? Either first name or surname. Thanks in advance, Mark PS. As this is a religious forum, I would like to point out that I have the greatest respect for all world religions, and the story will not portray any religion or religious group in a poor light. It's purely a work of fantasy.